Teaching AI

Helping AI learn and evolve

In October 2022, Alexandr Wang (CEO of Scale AI) interviewed Greg Brockman (CTO of OpenAI) on the past and future of AI models. Brockman reflected on his surprise at how well GPT-3 learned to generalize information:

The amount of data used to train GPT-3 is beyond human comprehension, as Brockman notes:

That picture of all the different things that it's seen in all these different configurations is almost unimaginable. There's no human who's been able to consume 40 terabytes worth of text…so I think that we just keep seeing surprises.

One example of this was in a recent study on predicting sex from photos of human retinas using deep learning:

AI is proven to exceed human capabilities in several areas, but it must have proper training in order to be truly effective.

Reflecting on roles

A lot of recent discussion has revolved around the potential of “AI Assistants” to change the way we work and live. But the less comfortable perspective to acknowledge is the extent to which humans are in effect assisting AI.

Luis Von Ahn (CEO of DuoLingo) invented reCAPTCHA, which was acquired by Google in September 2009. Here he talks about how those captcha codes not only helped verify humans on the Internet, but simultaneously served to crowdsource the digitization of books:

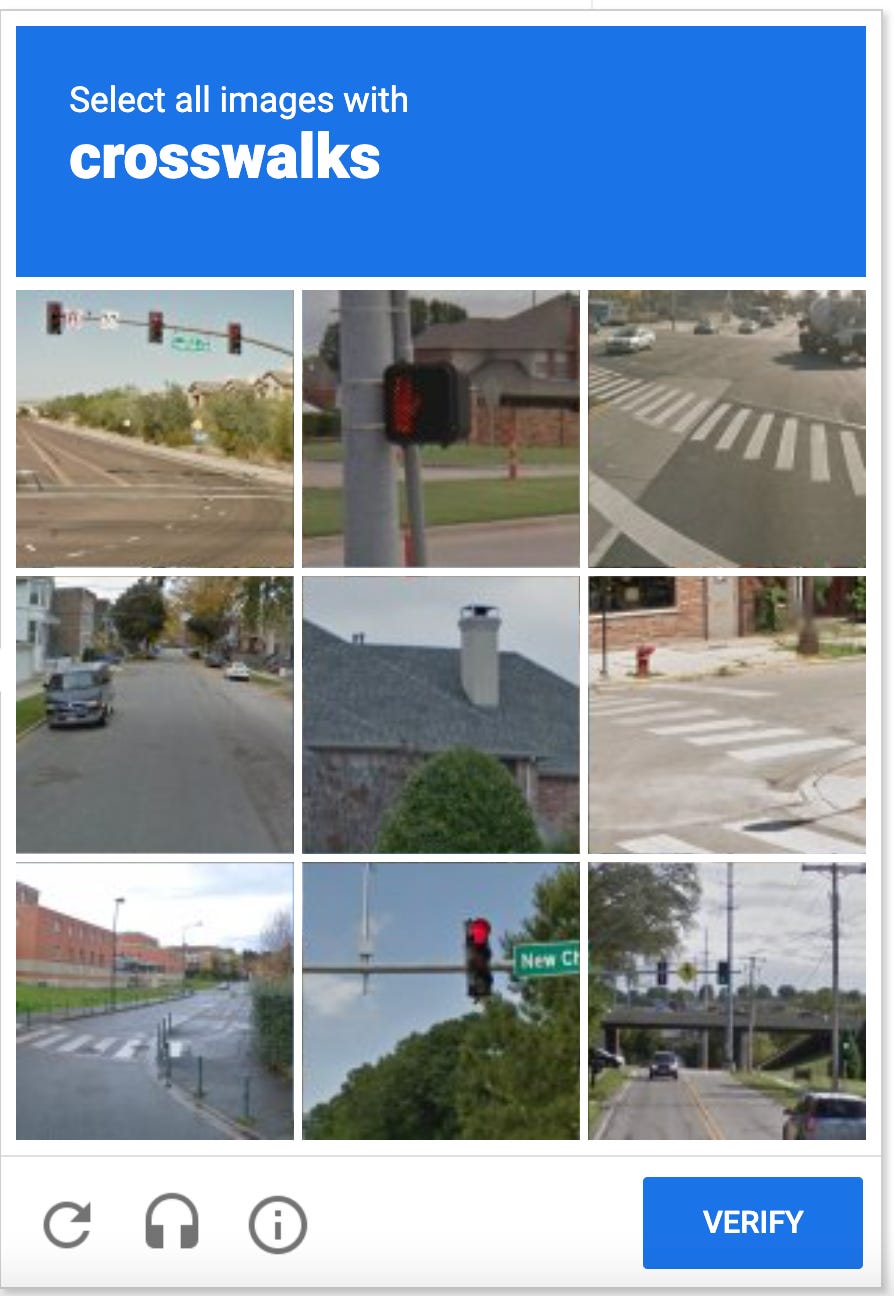

Now with the omnipresent reCAPTCHA v2, every time we do a captcha like this we are helping train AI for self-driving cars:

Aligning large groups of individuals using traditional methods is an immense challenge. But now, we are collectively contributing (often unwittingly) to the improvement of AI models.

There is something to be said about the emerging power of online collaboration — uniting strangers towards a common goal regardless of what background or beliefs they share. We are starting to see the next evolution of communities forming, making FaceBook groups and subreddits look meager compared to the potential of Internet institutions such as DAOs (Decentralized Autonomous Organizations) and network states.

It remains to be seen how these communities will evolve, but we will begin to observe ways in which decentralized yet highly aligned groups can crowdsource the training of AI models to accomplish various objectives. However, transparency should remain a priority in order to ensure that our data is properly used in the training of AI.

The cultivation of AI

In Ted Chiang’s novella The Lifecycle of Software Objects, a zoo-keeper gets hired by a software company to help train virtual pets called “digients” (digital entities).

It is a fascinating story with several thought-provoking themes, but the premise alone is worth reflecting on. Teaching digients is akin to raising a pet or a child, whereas the current approach to training AI is methodical and systematic. Ana, the main character in Chiang’s novella, even gets emotionally attached to these digital beings over the course of several years.

Alan Turing, one of the most famous computer scientists in history, wrote in 1950:

Instead of trying to produce a programme to simulate the adult mind, why not rather try to produce one which simulates the child’s? If this were then subjected to an appropriate course of education one would obtain the adult brain.

Training AI could soon become more intimate than simply feeding data models into a pipeline. We might start using words such as “nurturing” and “cultivating” AI in place of “training”. This phenomenon will accelerate as AI entities start to develop distinctive personalities and traits.

People from all walks of life are rapidly adopting AI to help accomplish a wide variety of tasks. But evidence of a symbiotic relationship is emerging. While the rise of AI assistants captures the headlines, let’s not forget the part we play in assisting AI. By recognizing our collective role as AI instructors, we can remain attentive to the direction in which AI is heading. And if we hold AI training processes accountable, we can help ensure that the models are used towards positive ends.